What makes an unusual design solution, and how have we selected the ten examples we are presenting in this article? Well, an ‘unusual design’ is clearly a flexible concept. As time and technology changes, so too does our notion of what a ‘normal’ aircraft design looks like. So, there is clearly a link to technology, and clearly early adopters of new technologies will be considered ‘unusual’ when they emerge. In this list, for example, we could have included the Messerschmitt Me 262, with its jet propulsion and swept wings. But with only a list of ten to work with, we chose the Me 163 instead, which featured not only a swept wing, but also rocket propulsion. Importantly, too, the Me 163 also pioneered a new role, that of the point-defence interceptor, and this links to another important reason for inclusion in this list, design to meet an extreme or specialist requirement.

What makes an unusual design solution, and how have we selected the ten examples we are presenting in this article? Well, an ‘unusual design’ is clearly a flexible concept. As time and technology changes, so too does our notion of what a ‘normal’ aircraft design looks like. So, there is clearly a link to technology, and clearly early adopters of new technologies will be considered ‘unusual’ when they emerge. In this list, for example, we could have included the Messerschmitt Me 262, with its jet propulsion and swept wings. But with only a list of ten to work with, we chose the Me 163 instead, which featured not only a swept wing, but also rocket propulsion. Importantly, too, the Me 163 also pioneered a new role, that of the point-defence interceptor, and this links to another important reason for inclusion in this list, design to meet an extreme or specialist requirement.

Several examples of aircraft addressing such extreme or specialist requirements are included in this list. In discussing these aircraft, we attempt to explain how the designers have responded to the requirement in shaping the aircraft, its propulsion or other systems to meet the requirement or role. Examples of such aircraft include the U-2 and SR-71 among others.

Finally, we have included some aircraft with more general requirements, but where, for specific reasons, unusual design choices have been made, leading to designs which differ markedly from other contemporary aircraft seeking to meet similar needs. These examples of original thinking are included as a reminder that innovation and originality remain a great aspect of the aviation business.

We have decided only to include in this list aircraft which could be regarded as successful, a consideration which eliminated numerous research aircraft, and also designs which, for whatever reason, had not been selected for operational use. However, there remain many others which met our criteria, and which we could easily have selected. If @Hush_Kit readers are interested in a further discussion of unusual design solutions, or if you vigorously disagree with our selections and would like to propose others – let us know through your comments on this piece.

By Jim & Ron Smith

10. Lockheed U-2 ‘Gaz’s prison bus’

The Lockheed U-2 was designed in 1954, in response to a requirement for an aircraft to overfly the USSR at an altitude of at least 70,000 ft. This requirement was prompted by events such as the detonation of the first Soviet Hydrogen Bomb in August 1953, years earlier than expected by the US. This showed that the US lacked accurate technical intelligence about the capabilities and intentions of the USSR, particularly its emerging capability to directly threaten the United States homeland.

Initial design work was directed to an Air Force requirement, but when Lockheed’s proposal, the CL-282, was rejected, Lockheed approached the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), resulting in the establishment of Project Aquatone, approved in December 1954. After rapid development, in great secrecy, by the Lockheed Skunk Works the U-2 made its first flight on 29 July 1955, and made its first operational mission over the USSR just under a year later on 4 July 1956.

Francis Gary Powers (right) with U-2 designer Kelly Johnson in 1966. Powers was a USAF fighter pilot recruited by the CIA in 1956 to fly civilian U-2 missions deep into Russia. Powers and other USAF Reserve pilots resigned their commissions to become civilians. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Despite hopes that the high altitude flightpath would prevent detection by Soviet radars, this proved not to be the case, and while overflights of the USSR would continue up to May 1960, these were terminated following the shooting down of Gary Powers’ U-2 over Sverdlovsk.

The initial role of the U-2 was high-altitude photographic intelligence gathering. Although flights over the USSR ceased from 1960, U-2s were used over Cuba in the context of the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, and over mainland China in 1963. The sensors developed for the aircraft were critical to its success, with high-resolution, long focal length cameras developed by Dr Edwin Land, specifically to achieve extraordinary resolution of ground targets from the operating altitude of 70,000 ft.

The roles of the aircraft gradually broadened to include Electronic Intelligence gathering (ELINT), atmospheric high-altitude research including sampling radio-active products of nuclear tests and testing various sensors. Along with these developments came significant weight increases and erosion of the aircraft’s altitude capability.

This led to the development of the second-generation U-2R, which is considerably larger than the original aircraft, and has greater thrust. The U-2R first flew in August 1967, and a further production batch, designated TR-1A were ordered in 1979. The role of the U-2R/TR-1A is now to deliver network-connected real-time intelligence via SATCOM for air and ground assets and command decision making. A wide range of sensors are available, and other capabilities include ELINT, Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) and Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) mapping.

The U-2 and U-2R/TR-1 are unusual because of their high-aspect ratio un-swept wings, their low-wing loading, and their two-point centre-line landing gear. The driving requirement for the design is to be able to operate at very-high altitude over extended ranges, carrying a significant sensor payload. The aircraft operate close to their maximum achievable altitude, and typically cruise near the maximum lift coefficient available from the wing. Because the aircraft operate at such high lift, it is important that their lift dependent drag is minimised, as this will minimise thrust requirements and maximise range. The distinctive high-aspect ratio wing is used to achieve this, and it is notable that other aircraft with similar high altitude mission requirements, such as the RQ-4 Global Hawk and the Myasishchev M-17 and M-55 adopt a similar approach.

At high altitude, the speed of sound is less than at sea level, and high local Mach numbers occur on the wing as a result of its pressure distribution at high lift. In the cruise the aircraft operates in an approximately 10 kt window where it can fly above its low-speed stall, without high local Mach numbers causing a high-speed, or compressibility, stall.

The extreme requirements, for the aircraft to deliver its mission at very high-altitude, result in a number of other operational complications. Structural margins on the aircraft are reduced to achieve a lighter structure; the thrust required at high altitude far exceeds the thrust required at lower altitudes, and an extremely steep climb on take-off is usually used, both to limit loads on the airframe, and to limit exposure of the mission to prying eyes.

The U-2 is notorious for being difficult to land, and operationally is generally talked down onto the runway by an external observer following the aircraft in a high-speed car. This is because precise handling is required to achieve the correct landing attitude and to avoid excessive bounce or float on landing.

The aircraft first flew in 1955, and remains in service. More than 100 aircraft of all variants were built, and there are currently no plans for its retirement.

9. Tupolev Tu-95 and Tu-142 ‘Bear’ ‘The Tupo-leviathan’

The Tu-95 Bear was designed as a long-range strategic bomber, able to deliver thermonuclear weapons over a very long range. Since first flying in 1955, the aircraft has remained in service, and has been upgraded and modified to deliver a number of roles. The origins of the aircraft go back to the Second World War – it is no coincidence that the fuselage diameter is the same as that of the B-29 Superfortress, as the DNA of the Bear goes back to the Tupolev Tu-4 copy of the Boeing design. Developments of that aircraft, the Tu-80 and Tu-85, led to the Tu-95 when it was realised that the use of powerful and efficient turbo-prop engines could allow a transformation in speed, range and payload to be achieved.

Today, the principal roles of the Bear are the delivery of a variety of nuclear and conventional cruise missiles, allowing strategic power projection, with a global reach enabled by air-to-air refuelling. In addition, specialist variants are, or have been, used for electronic intelligence gathering, maritime reconnaissance and targeting, Anti-Submarine Warfare and as long-range communications platforms.

The Bear is unusual because it uses a unique combination of swept wings and very large turbo-prop engines. The Tu-142 version was developed initially for maritime reconnaissance and ASW, and uses the 14,795 hp Kuznetsov NK-12M powerplant, driving 18ft 4in (5.59m) diameter contra-rotating propellers, and also has an extended fuselage. The propellers are operated at a very coarse pitch setting, which allows them to generate the necessary cruise thrust while operating at low rpm, avoiding high blade-tip Mach numbers. Combined with the wing sweep of 37 deg (at ¼ chord), these powerplants and the configuration enable the aircraft to achieve both high speed and very-long range.

Quoted performance figures vary depending on source and variant. A maximum speed of 450-500kt with full payload, and a maximum unrefuelled range with a 25,000 lb weapons load of 7,800 miles, or 9,300 miles with no payload have been stated.

The requirements that drove the development of the Tu-95/142 were, as is normal for a strategic bomber, range, speed and payload. The aircraft was developed at a time when USSR turbo-fan engine development was insufficiently mature to match the thrust and fuel economy available through use of turbine-driven large-diameter contra-props. The use of slow-rotating contra-props and a swept wing enables high-speed, in addition to the range and payload conferred by the large size of the aircraft and its economical powerplant. The initial engine power of 9,750 hp was increased to 12,000 hp in the production Tu-20, and to 14,795 hp in the Tu-142. The Kuznetsov NK-12M is easily the most powerful turbo-prop engine built to date.

The aircraft has been an outstanding and long-lived success for its designers and operators, remaining in active service with the Russian Air and Naval Aviation Forces. It was also operated in limited numbers by the Indian Navy and Ukraine. Wikipedia lists more than twenty variants of the aircraft, and notes that many other sub-variants have been used.

8. Shin Meiwa Flying Boats ‘Hyper Sunderland’

The Japanese company Shin Meiwa (later renamed ShinMaywa) have produced a series of large amphibious flying boats for use on anti-submarine patrols (PS-1) and search and rescue operations (US-1A and US-2). The PS-1 was a pure flying boat, but carried its own retractable beaching gear. The US-1A and US-2 are amphibian flying boats with retractable undercarriages and can operate from hard runways, or from the open ocean.

In the 1950s, the Shin Meiwa company began to investigate how to create a flying boat of improved performance that could provide year-round operations in the seas around Japan. To achieve this, the performance requirements are somewhat extreme, combining a range of some 2,000 nm, carrying extensive mission equipment and the ability to routinely operate with wave heights up to 3.0 metres. This is coupled with the ability to take-off and land in extremely short distances at maximum weight.

Shin Meiwa initially extensively modified a Grumman HU-16 Albatross as an experimental aircraft to evolve their ideas and to demonstrate to the Japanese authorities. This aircraft, the UF-XS, pioneered many of the features later incorporated on the operational designs.

After several years of development, in 1966 the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) awarded a contract for the development of an anti-submarine patrol flying boat. Two PS-X prototypes were built, one of which demonstrated the ability to land successfully in four-metre high waves during trials in 1968.

As a result, a production order was placed for 21 PS-1 aircraft. The PS-1 flying boat was powered by four 3,060 shp General Electric T64-IHI-10 turboprop engines, built under license by Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries (IHI), supplemented by an additional 1,250 shp General Electric (GE) T58 turboshaft engine solely to provide blowing air for the boundary layer control system fitted to the high-lift flaps, elevator and rudder control surfaces.

The PS-1 is a large aircraft, with a span of 108 ft 9 in and a length of 109 ft. Its maximum weight is 94,800 lb (43,000 kg). The effectiveness of the BLC system is such that the aircraft can take-off from a calm sea in 250m and land in 180m. Nine crew are carried, comprising pilot and copilot; flight engineer; radio operator; radar operator; MAD operator; two sonar operators; and a tactical coordinator. The PS-1 was withdrawn from service in 1989, having been replaced in the ASW role by the Lockheed P-3 Orion.

The JMSDF requested the development of a search-and-rescue (SAR) variant. The resultant aircraft, designated US-1 deleted most of the PS-1’s mission equipment (other than the search radar), allowing a considerable increase in fuel capacity.

A large sliding door was built into the starboard side of the aircraft to allow launch and recovery of an inflatable rescue dinghy, with a hoist fitted above the sliding door. The US-1 had a crew of eight, including pilot; copilot; flight engineer; navigator; radio operator; radar operator; and two observers. Up to five medics or rescue divers could also be carried. The aircraft could accommodate 12 stretchers and three sitting passengers, or 36 sitting passengers.

The US-1 has an amphibious capability with a fully retractable undercarriage and was first flown on 15 October 1974, with a total of twenty aircraft being procured. After the seventh aircraft, an uprated version of the T64 engine was used rated at 3,490 shp, all aircraft being modified to this US-1A standard. Take-off weight was increased to 45,000 kg.

The final variant of the aircraft is the ShinMaywa US-2, which was first flown on 18 December 2003. This type has several aerodynamic refinements and a pressurised upper cabin, together with improved avionics and a new search radar. Power is provided by four Rolls-Royce AE2100 engines, each of 4,592 shp, driving six-bladed propellers. The APU is replaced by a 1,360 shp LHTEC CTS800-4K turboshaft. Take-off weight is increased to 47,700 kg and range to 2,500 nm. The US-2 can take-off at maximum weight from a hard runway with a ground run of 500 metres. Planned procurement by Japan is fourteen aircraft, and sales of the type have been discussed with India, Indonesia, Thailand and Greece, although no overseas sales have so far been reported.

A number of videos showing the impressive take-off performance of the aircraft can be found on the internet – see, for example:

7. Kaman helicopters ‘Intermeshion’

The Kaman helicopter family is a series of helicopters with twin intermeshing rotors that make use of a novel control system. The design is particularly suited for operations that require primarily hovering and low speed flight in roles such as cargo and freight transfer between ships, plane guard duties and aircraft crash rescue and firefighting. More recently, the civilian K-Max has found a role in the civilian heavy lift market.

Charles H Kaman was an engineer working for United Aircraft (the parent company of Sikorsky) at Hamilton Standard who developed novel ideas about how to control a helicopter rotor. After establishing that United Aircraft would not support a second helicopter enterprise within their business, Kaman left and set up the Kaman Aircraft Corporation on 12 December 1945.

There are two main features to the design, the rotor configuration, and the flight control system employed.

• Rotor Configuration: The Kaman family of helicopters feature two intermeshing contra-rotating two-blade rotors, geared together so that they cannot rotate independently. The toque of the two rotors cancels each other out, so that no tail rotor (and associated supporting structure) is required. This configuration originated with the German Flettner designs (such as the FL282 Kolibri) and was also investigated by the Kellet Aircraft Corporation in the United States.

• Rotor Control: rather than use conventional cyclic and collective pitch control by using pitch-change bearings at the blade root with pitch links controlled by a swashplate, Kaman decided to use a much-simplified head with no pitch change bearings. Instead, control was achieved by fitting controllable servo flaps at about three-quarter radius on each blade. Deflection of the flaps caused the blade to twist, increasing or reducing its lift. Symmetric operation of the flaps applied collective pitch; differential operation resulted in cyclic pitch control. This system is unique to Kaman’s designs, and its operation is analogous to the warping wing controls used in some pioneer fixed wing aircraft.

The main requirements leading to Kaman’s design were light weight, efficient hover performance and effective control independent of wind direction. The configuration saves weight by eliminating the weight and power penalties associated with the rear fuselage, tail rotor and associated gearboxes and drive shafts.

The low inertia of the servo-flap systems means that control loads are minimal and responsiveness is excellent, meaning that Kaman rotors can be controlled manually and therefore do not need hydraulic control actuators. The presence of two separate rotor hubs and their support pylons introduces a drag penalty, but this is not a major consideration in the main roles for which these types have been used.

By any measure, the Kaman intermeshing rotor designs have been very successful and established some notable firsts, including the world’s first turbine powered helicopter, America’s first twin turbine helicopter and the world’s first remotely-controlled helicopter.

After two prototypes (K-125, K-190), production commenced with the K-225. 11 were built, primarily for crop dusting, with one exported to Turkey and four going to the US services. One K-225 was experimentally fitted with a Boeing 502-2 turboshaft engine, becoming the world’s first turbine powered helicopter, when flown of 11 December 1951.

Military acquisition built up with the 235 hp HTK-1, 29 being acquired by the US Marines (plus one HTK-1K modified for pilotless flight as the world’s first drone helicopter). One was modified with twin Boeing 502-2 turboshaft engines, becoming the first US twin-turbine helicopter when it flew on 26 March 1954.

Production continued with 81 HOK-1 (US Marines OH-43D), 24 HUK-1 (US Navy UH-43C) and 18 HH-43A (USAF). These aircraft were all powered by the 600 hp Pratt & Witney R-1340 piston engine.

The larger HH-43B and HH-43F followed for rescue and fire-fighting duties. The HH-43B was primarily used by the USAF. First flown on1 November 1958 and powered by an 860 shp Lycoming T53-L1B, 208 HH-43B were built, the type also being supplied to Colombia, Burma, Morocco, Pakistan, and Thailand.

The HH-43F provided better performance in hot and high conditions, being powered by a 1,150 shp Lycoming T53-L-11A flat rated to 825 shp. The HH-43F was first flown in August 1964, with 32 being supplied to Iran and 5 to Burma. Two pilotless QH-43G were also built, together with a single civil prototype designated K-1125.

The final design in this family is the Kaman K-1200 K-Max Commercial single seat heavy lift and fire-fighting helicopter. This type remains in production with some 53 built. The K-Max was first flown on 23 December 1991 and is powered by one Honeywell T53-17 turboshaft, flat rated to 1,500 shp for take-off and 1,350 shp in flight. The K-Max has 6000 lb external lift capacity, exceeding the aircraft’s empty weight of 5,145 lb.

Nearly 470 Kaman intermeshing rotor helicopters have been built, including two prototypes (K-125, K-190), eleven K-225, 152 piston-powered HTK, HOK, HUK & HH-43A, 248 turbine-powered HH-43B, HH-43F, QH-43G and K-1125, and (to date) 53 K-1200 K-Max.

6. English Electric Lightning ‘The Double Decktric’

Credit: BAE Systems

The English Electric Lightning was developed as a specialist point-defence interceptor. The specific requirement was to defend the RAF nuclear deterrent V-bomber bases, against attack by the USSR. The term ‘point-defence’ is used because the requirement was to defend specific locations, close to the aircraft’s operating base, by intercepting and shooting down attacking aircraft. The development aircraft (P-1A) first flew in August 1954, and the Lightning entered service with the RAF in 1960, serving until 1988.

The Lightning’s Air Defence role evolved over time, in response to technical developments in threat aircraft and missiles. As air-launched cruise missile systems were developed, allowing threat bombers to launch their weapons at significant stand-off range, it became apparent that point-defence interception was no longer a viable approach. Consequently, the Lightning was developed to provide additional fuel in the wing, and in a larger under-fuselage fuel tank, and the role of the aircraft switched to combat air patrol, supported by aerial tankers. In addition, the nuclear deterrence role was transferred to the Royal Navy missile submarine force, removing the specific requirement for a point-defence aircraft.

Credit: BAE Systems

Three main variants were developed. The initial F1/F1A used the 14,430 lb thrust Avon 200 engine, and had the distinction of being able to take-off, cruise and land on either of its two engines, and could even maintain supersonic flight on one engine. The F1A added air-refuelling capability to the F1. Armament was 2 30mm cannon and 2 Firestreak air-to-air missiles.

The F2 was an interim version with an improved reheat system, and the next major variant was the F3, which introduced Avon 301 engines with 16,300 lb thrust, and an enlarged fin. The F3 could carry either Firestreak, or the larger Red Top missile, but the cannon armament was deleted. The F3A introduced an enlarged ventral fuel tank.

The final variant, the F6, introduced a new wing with extended and cambered leading edges, which allowed more fuel to be carried, and also reduced subsonic drag. The cannon armament, which had been deleted for the F3, was re-introduced for the F6, mounted in the front of the significantly enlarged belly fuel tank, which had been introduced in the F3A.

Credit: BAE Systems

Unusual features of the aircraft were the very highly-swept wing, and the arrangement of the two engines, which were stacked in the fuselage, with the lower engine forward of the upper one. This engine arrangement was fed from a common nose inlet, featuring a central cone, which contained the aircraft’s Air Intercept radar.

The configuration of the aircraft was driven by the need to achieve a very rapid rate of climb, and high intercept speed, to minimise the time to achieve an interception from a ground alert status. This placed an emphasis on rapid climb to height, which is a driver for thrust to weight ratio and low drag; and high-speed dash, which requires low supersonic wave drag. High sweep back, minimal frontal area, powerful engines, and light weight, including minimal fuel in early versions, are all consequences of this point-defence interception requirement. The aircraft ws renowned for its excellent handling, and for its ability to cruise at supersonic speeds in dry thrust.

Quoted performance figures for the Lightning include a climb rate of 20,000 ft/min, a maximum speed of Mach 2.0, and the ability to climb to 36,000 ft in less than three minutes.

The Lightning was operational with the RAF from 1960 to 1988, and 337 were built. The aircraft was also used by Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

5. Transavia PL-12 Airtruk ‘Pellarini’s Flying Mango’

The Transavia Airtruk is a crop-spraying aircraft with a most extraordinary configuration. The aircraft has a truncated pod fuselage with the pilot sat high and well forward above, and only just behind, the engine. The main 36 cubic feet chemical hopper is immediately behind and below the pilot and there is space in the truncated fairing behind the hopper for the carriage of two ground crew. Power of the standard PL-12 design is provided by a 300 hp Continental IO-520-D piston engine.

Rather than being at the end of a conventional rear fuselage, the rear control surfaces are carried at the end of two well-separated tail booms, each of which carries a fin and rudder topped by a high set tailplane and elevator. The two tail booms attach at the mid-span point on the port and starboard upper wings of the sesquiplane biplane wing structure. The spacing of the tail booms provides a clear space of 11 ft 5 in width between the tailplanes.

The configuration is a classic case of the engineering form following function. Some of the main advantages are listed below:

• The space between the tail booms allows rapid direct filling of the chemical hopper from a truck approaching from behind the aircraft

• The high seating position provides exceptional forward view from the pilot and prevents them from being crushed between the engine and hopper in the case of an accident

• The absence of the rear fuselage structure saves weight and means that this area cannot be contaminated by chemicals

• The strut-braced sesquiplane wing structure is structurally efficient and provides plenty of wing area for manoeuvrability and low stall speed (60 mph for the standard aircraft)

• A wide track (8 ft 0 in) tricycle undercarriage is provided, with the main gear mounted from the lower wing

• The aircraft empty weight is 1,850 lb, while the maximum weight in agricultural operations is 4,090 lb, providing an impressive disposable load of 2,240 lb (or 120% of the empty weight)

• The fuselage pod allows the aircraft to carry its ground crew on board, while positioning to and from operational sites

Variants include the PL-12(U) utility aircraft, which first flew in December 1970. The chemical hopper is removed from this aircraft and the reconfigured cabin volume allows four passengers to be carried in the lower cabin, with one further passenger rearward-facing behind the pilot. The T-300 Skyfarmer has a 300 hp Lycoming IO-540-KIA5 engine, while the T-320 uses a 320 hp Continental Tiara 6-320-2B.

A total of some 118 aircraft were built, with aircraft operating in Australia, Denmark, India, Kenya, Malaysia, New Zealand, South Africa and Thailand. A number of aircraft were assembled in New Zealand by Flight Engineers Ltd.

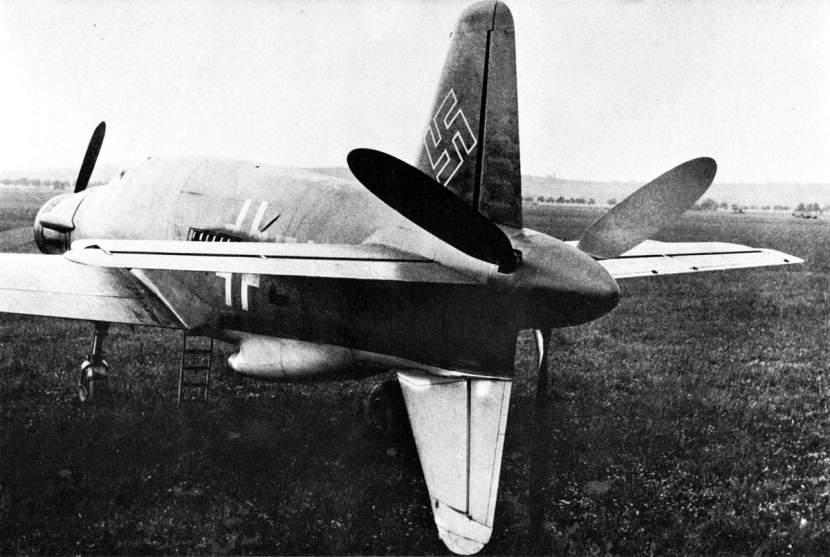

4. Dornier Do 335 ‘Pfeil’ ‘The X-Pfeils’

The Dornier 335 Pfeil (Arrow) has been described as ‘the most audacious fighter of the Second World War’ . The Pfeil was produced in three variants – Fighter-Bomber, Zerstorer (Night Fighter) and trainer. As, a twin-engine fighter-bomber, its role is broadly comparable with the de Havilland Mosquito FB VI. Like that aircraft, it was both heavily armed, with one 30-mm cannon and two-15 mm cannon, and had both an internal weapons bay capable of carrying two 250 kg bombs, and external hardpoints for a further two 250 kg bombs. The more heavily armed Zerstorer had three 30-mm cannon and two 20-mm cannon, but used the internal weapons bay as an additional fuel tank.

The Mosquito FB VI Series 2 carried the same bomb load, but was more heavily armed, with four 20-mm cannon and four Browning machine guns, and had greater range, but had a maximum speed some 100 mph slower than the Pfeil.

The Pfeil featured a unique engine arrangement, with both a conventional front-mounted engine, and a centre-fuselage engine driving a pusher propeller located behind a cruciform tail. This tandem-engine arrangement minimised the frontal area of the aircraft, while retaining a clean wing, with sufficient volume available for an internal weapons bay. In addition, avoiding a twin-boom arrangement would have reduced roll inertia and improved manoeuvrability.

The driving requirements were to maximise speed, manoeuvrability and payload (gun armament and bombs). One of the fastest piston-engine fighters ever built, the Pfeil is described by Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown as ‘very fast and quite manoeuvrable’ and as ‘the fastest piston engined machine in the world’. The aircraft is unusual because the tandem engine arrangement is a key enabler for the high speed achieved by the aircraft.

An indication of the aircraft’s capabilities is given by this description of an attempt by two Tempests to engage a Dornier Pfeil at low altitude .

“Throttle full open, I tried to cut inside his turn, but he was moving astonishingly fast. Longley was better placed and fired at him, but without effect. The strange aircraft completed his turn and flew off at full speed. He really was an extraordinary looking customer. His tailplane was cruciform, and it looked as if he had not only a normal propeller in front but on top of that a pusher propeller right in the tail, behind the rudder. His front engine was an ‘in line’ with a cowling like a DB603 in a Focke-Wulf Ta 152C with a ring-shaped radiator; the other engine was buried in the fuselage, behind the pilot. The two long grey trails in his slipstream showed he was using a supercharger, and the thread of white escaping from his exhausts showed that he was using GM-1. I toyed with the idea of bringing my supercharger into action, but even with 3,040 hp we wouldn’t be able to get him. We were doing nearly 500 mph and he was easily gaining on us.”

The Dornier Pfeil was completed too late in the war to achieve true operational service, although it had been used for operational trials and tactics development, and clearly experienced at least one combat engagement. A total of 11 production aircraft, two trainers and 12 prototypes were completed, with a further 15 aircraft in final assembly when the factory was captured. The aircraft is included in this list because, had circumstances allowed, it would clearly have been used operationally by the Luftwaffe.

3. Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet ‘Taschenrakete’

The Messerschmitt Me 163 was a small rocket propelled air defence aircraft, and was one of the most dramatic developments in wartime combat aircraft design. Its role was to deliver what was itself a new concept, point defence interception. An example of its operational use was the defence of synthetic oil manufacturing facilities against Allied bombers.

The ground-breaking features of the aircraft included its tailless swept-wing airframe, liquid-fuelled rocket propulsion, and its small size and light weight. To reduce weight the Me 163 dispensed with a conventional undercarriage, taking off using a wheeled dolly, dropped once airborne, and landing using a simple skid. The armament carried was two 30-mm cannon.

As a point-defence interceptor, the aircraft needs to achieve high climb rate to reach operational altitude quickly, and high speed to achieve a rapid interception. As discussed in another piece for Hush-Kit on aircraft design, climb rate is maximised by combining high thrust with low weight and drag. The Me 163 achieved its extraordinary climb rate through its rocket propulsion, minimum size and weight airframe, and its use of swept wings.

The climb performance of the Me 163 was probably not matched in an operational aircraft until the introduction to service of the Lightning. The extraordinary test pilot, Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown, reports reaching 32,000 ft in 2 ¼ minutes in his first powered flight in the aircraft . Fully operational aircraft could climb to 39,500 ft in 3 ½ minutes, and attaining a maximum speed of 596 mph.

The Me 163 was operational from July 1944 to the end of the Second World War. Its success was somewhat limited, however, despite being armed with twin 30mm cannon. The very high speeds achieved by the aircraft resulted in very rapid closing rates against bomber targets, even in a stern attack. Combined with a relatively low rate of fire from its cannon, this resulted in firing opportunities typically limited to a few seconds only. This problem was exacerbated by the low powered endurance, which was typically less than 5 minutes at altitude. More than 300 aircraft were delivered.

2. Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird ‘Trisonic Turdus’

The Lockheed A-12 and SR-71 are high-altitude strategic reconnaissance aircraft, capable of sustained operation at more than Mach 3.0. They were designed to conduct intelligence gathering and reconnaissance flights over unfriendly territories at altitudes and speeds that make them difficult, if not impossible, to intercept. An additional variant operated as a drone carrier aircraft, while the YF-12 air combat variant was never deployed operationally.

These aircraft feature unique configurations and construction materials, driven by high-speed and high-altitude requirements to be out of reach of SAM-systems. This leads to a highly-swept blended delta configuration with twin variable by-pass turbo-ramjet engines. These aircraft were also designed for reduced radar signature with RAM wedges incorporated in leading and trailing edges.\

The aerodynamic heating, encountered at cruise speeds in excess of Mach 3, means that Aluminium cannot be used for their structures. As a result, the main structural material is Titanium, which is notoriously difficult to work, but can withstand the high skin temperatures. The outer layer of cockpit glazing is of quartz, to withstand local temperatures in excess of 300 degrees Celsius.

The Lockheed A-12 was developed for the CIA as a secret project of Kelly Johnson’s Lockheed ‘Skunk Works’. The A-12 was a single seat aircraft and was the precursor to the twin-seat Lockheed YF-12 prototype interceptor, the M-21 (launcher for the supersonic D-21 drone), and the SR-71 Blackbird. The codename for the A-12 programme was Oxcart and the aircraft flew for the first time on 26 April 1962. Thirteen A-12 aircraft were built, together with two M-21 two-seat aircraft designed to carry and launch the D-21 supersonic ramjet-powered drone.

Three prototype armed YF-12A were built. These were twin-seat aircraft armed with the AIM-47 Falcon air-to-air missile. The YF-12A can be distinguished by its nose radar, cut-back chines and twin ventral fins.

These aircraft were followed by the Lockheed SR-71 two seat strategic reconnaissance aircraft, which was slightly stretched (increased in length by 5 ft 2 in) and had a significantly higher maximum weight (172,000 lb versus 117,000 lb) than the A-12, together with aerodynamic refinements to the forward chine shapes.

The SR-71 flew for the first time on 22 December 1964 attaining a speed in excess of 1,000 mph on its first flight. (Ref: Lockheed’s Skunk Works: The First Fifty Years, Jay Miller). The SR-71 was used to set absolute speed and altitude records and several point-to-point speed records. These included an absolute speed record of 2,193.17 mph and 2,092.29 mph over a 1,000 km closed circuit, with a maximum sustained altitude of 85,069 ft. In operations, the aircraft routinely cruised at Mach 3.2 at altitudes above 75,000 ft.

Production comprised 13 A-12 and 2 M-21 (drone carriage); 3 YF-12A and 31 SR-71 plus one aircraft from salvaged YF-12A and SR-71 static test article. Thrust for the SR-71 was provided by two 34,000lb Pratt & Whitney JT11D-20A (J58).

No aircraft were shot down during operational sorties that included flights over Libya, Vietnam, Laos, North Korea, the Kola Peninsula and the Baltic and other areas of conflict such as the Yom Kippur War.

The SR-71 was initially withdrawn from service in 1989, with the last operational mission October 1989. However, the decision was taken in September 1994 to reactivate three aircraft, with the first example becoming operational in June 1995. The last SR-71 flight being made on 9 October 1999. During its operational career with Strategic Air Command, the SR-71 accumulated more than 50,000 flight hours, nearly 12,000 of these being at speeds in excess of Mach 3.

1. Lockheed F-117 ‘The Woblin’ Goblin’

The Lockheed F-117 broke new ground as the first operational low-observable tactical strike aircraft. The outcome of a process which started with a DARPA study into reduced signature fighters in 1974. Out of this emerged the radical ‘Have Blue’ concept demonstrator program, and the F-117 itself, which achieved initial operational capability in 1983.

The aircraft’s role has been the attack of heavily-defended, high-value targets, at night, using precision laser guided bombs, carried in an internal weapons bay. The F-117 was the first true ‘stealth’ aircraft, designed to counter radar and infra-red sensors, while minimising its own electronic emissions. Every feature of the aircraft is influenced by the approach taken to minimise these signatures.

A key element in the management of radar and IR signature so as to avoid detection and prevent successful engagement was the ability to predict the signature of the aircraft, and to design a flyable shape with low signature. At the time of its development, signature prediction capabilities were limited, but it was realised that if a flyable aircraft could be developed using a finite number of flat surfaces, then it would be possible to predict and minimise its signature.

The benefit of using a faceted design, with careful control of geometry to align edges and surfaces, is that radar returns can be essentially limited to a number of ‘flashes’ with very narrow dispersion, directed at a large angle to the illuminating radar. As a result, not only would a F-117 be difficult to detect, it would also be very difficult to track. The unique faceted, highly-swept configuration of the F-117, with its triangular fuselage cross-section, is a consequence of this design approach.

Additional features of the aircraft contributing to its low signatures include gridding of the intakes and sensor window, and gold flashing on the canopy, to prevent radar reflection from these cavities; a large weapons bay to allow all stores to be carried internally; a narrow letter-box exhaust located on the upper surface of the aircraft to minimise infra-red signature; and retractable communications aerials.

After take-off on a mission, these aerials are retracted, and the aircraft performs the mission with no external communication being used. Mission planning is critical, as is a knowledge of the ‘Electronic Order of Battle’ – the location and nature of any radar systems which might detect the aircraft. This information is used to plan ingress and egress to avoid directing radar return ‘flashes’ at threat sensors, minimising the likelihood of detection or tracking.